Back Segregacio en rekonstruo Esperanto Segregación en la reconstrucción Spanish د بيا رغونې له پړاو وروسته د رايې ورکولو له حق نه بې برخې کول Pashto/Pushto 後重建時期的剝奪投票權 Chinese

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era[2] in the United States, especially in the Southern United States, was based on a series of laws, new constitutions, and practices in the South that were deliberately used to prevent black citizens from registering to vote and voting. These measures were enacted by the former Confederate states at the turn of the 20th century. Efforts were also made in Maryland, Kentucky, and Oklahoma.[3] Their actions were designed to thwart the objective of the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, ratified in 1870, which prohibited states from depriving voters of their voting rights based on race.[4] The laws were frequently written in ways to be ostensibly non-racial on paper (and thus not violate the Fifteenth Amendment), but were implemented in ways that selectively suppressed black voters apart from other voters.[5]

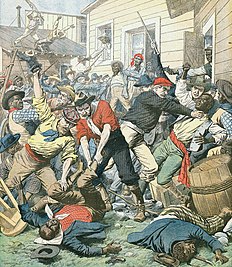

Beginning in the 1870s, white racists had used violence by domestic terrorism groups (such as the Ku Klux Klan), as well as fraud, to suppress black voters. After regaining control of the state legislatures, Southern Democrats were alarmed by a late 19th-century alliance between Republicans and Populists that cost them some elections. After achieving control of state legislatures, white conservatives added to previous efforts and achieved widespread disfranchisement by law: from 1890 to 1908, Southern state legislatures passed new constitutions, constitutional amendments, and laws that made voter registration and voting more difficult, especially when administered by white staff in a discriminatory way. They succeeded in disenfranchising most of the black citizens, as well as many poor whites in the South, and voter rolls dropped dramatically in each state. The Republican Party was nearly eliminated in the region for decades, and the Southern Democrats established one-party control throughout the Southern United States.[6]

In 1912, the Republican Party was split when Theodore Roosevelt ran against William Howard Taft, the party nominee. In the South by this time, the Republican Party had been hollowed out by the disfranchisement of African Americans, who were mostly excluded from voting. Democrat Woodrow Wilson was elected as the first southern President since 1848. He was re-elected in 1916, in a much closer presidential contest. During his first term, Wilson satisfied the request of Southerners in his cabinet and instituted overt racial segregation throughout federal government workplaces, as well as racial discrimination in hiring. During World War I, American military forces were segregated, with black soldiers poorly trained and equipped.

Disfranchisement had far-reaching effects in the United States Congress, where the Democratic Solid South enjoyed "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953".[nb 2][7] Also, the Democratic dominance in the South meant that southern senators and representatives became entrenched in Congress. They favored seniority privileges in Congress, which became the standard by 1920, and Southerners controlled chairmanships of important committees, as well as the leadership of the national Democratic Party.[7] During the Great Depression, legislation establishing numerous national social programs were passed without the representation of African Americans, leading to gaps in program coverage and discrimination against them in operations. In addition, because black Southerners were not listed on local voter rolls, they were automatically excluded from serving in local courts. Juries were all white across the South.

Political disfranchisement did not end until after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which authorized the federal government to monitor voter registration practices and elections where populations were historically underrepresented and to enforce constitutional voting rights. The challenge to voting rights has continued into the 21st century, as shown by numerous court cases in 2016 alone, though attempts to restrict voting rights for political advantage have not been confined to the Southern United States. Another method of seeking political advantage through the voting system is the gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, as was the case of North Carolina, which in January 2018 was declared by a federal court to be unconstitutional.[8] Such cases are expected to reach the Supreme Court of the United States.[9]

- ^ "The two platforms: About this item". www.loc.gov. Library of Congress. 1866. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Disenfranchise vs. disfranchise". Grammarist. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ^ World, Debbie Jackson and Hilary Pittman (November 3, 2016). "Throwback Tulsa: Black Oklahomans denied voting rights for decades". Tulsa World. Archived from the original on November 22, 2021.

- ^ Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888-1908 (U of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- ^ Keele, Luke; Cubbison, William; White, Ismail (2021). "Suppressing Black Votes: A Historical Case Study of Voting Restrictions in Louisiana". American Political Science Review. 115 (2): 694–700. doi:10.1017/S0003055421000034. ISSN 0003-0554. S2CID 232422468.

- ^ Valelly, Richard M.; The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement University of Chicago Press, 2009, pp. 134-139 ISBN 9780226845302

- ^ a b Valelly; The Two Reconstructions; pp. 146-147

- ^ Blinder, Alan; Wines, Michael (9 January 2018). "North Carolina Is Ordered to Redraw Its Congressional Map". The New York Times.

- ^ Wines, Michael (11 January 2018). "Is Partisan Gerrymandering Legal? Why the Courts Are Divided". The New York Times.

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search